“…the result is institutionalized processes that prevent IT acquisitions from fully meeting operational needs while failing to defend against peer-capable cyber security threats!”

Measuring inputs does not equal effective outputs!

It is difficult to measure the output success of a military system acquisition before that acquisition is delivered. For this reason the defense acquisition system is built around a set of input measures aligned across requirements, budgets, and acquisition oversight. In addition, the acquisition workforce is saddled with well meaning organizational efficiency input measures such as travel restrictions, reduced support contractor headcount, more competitive contracts, and even cost controls on the amount government is willing to pay for system development contractors. The general belief is that these input measures are necessary for our Government to be a good steward of public funds, and in the case of the DoD, to more efficiently buy military capability in the face of shrinking budgets.

Unfortunately for DoD information technology (IT) acquisition, the result is institutionalized processes that prevent IT acquisitions from fully meeting operational needs while failing to defend against peer-capable cyber security threats! The reason is that measuring inputs requires oversight organizations that gather and track input measures. Confident of their value add, these organizations often slow down acquisition decisions with little improvement to delivered capability. Because time is directly related to cost, time consuming processes add more cost to IT acquisition programs than well meaning efficiencies can offset. The result is increased cost, delayed capability delivery, and less effective military capability!

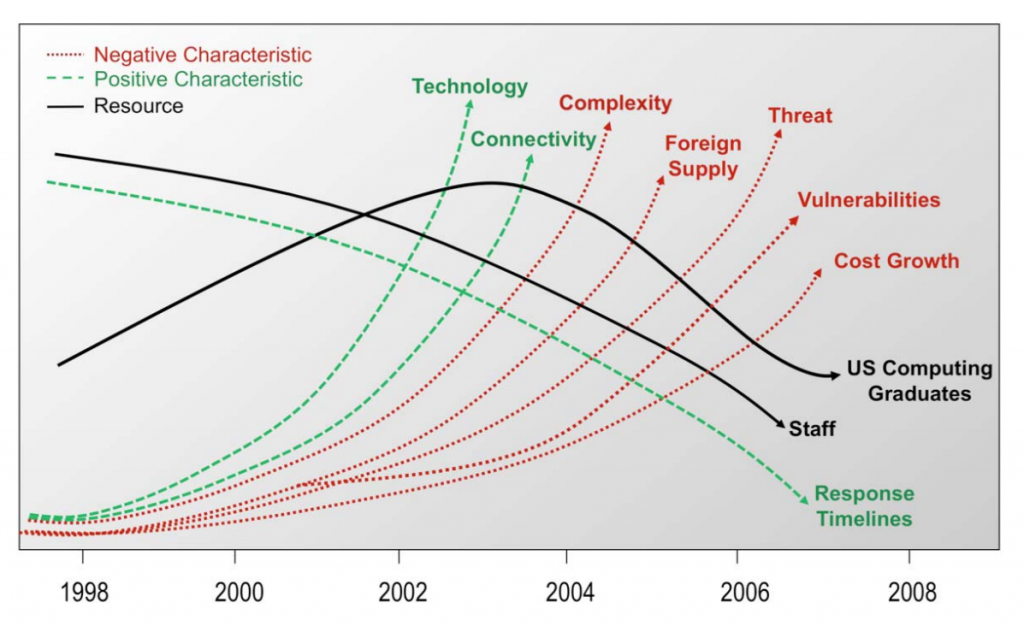

The March 2009 Defense Science Board study, DoD Policies and Procedures for the Acquisition of Information Technology, makes this case while detailing the added challenges of taking advantage of rapid IT technology change, pacing cyber threat vulnerabilities, and dealing with the inadequate availability of qualified IT engineers and managers.

“This decline in U.S. software talent is occurring in the face of increased demand. The gap between degreed professionals and job openings is growing, most notably in mathematics and computer science where only half the annual job openings can be satisfied by newly degreed students…”

The below chart depicts what this DSB report describes as the Perfect IT Storm. It shows that even in 2009, the growth of IT technology and networked connectivity was being challenged by growing system complexity, foreign supply to include counterfeit components, cyber threats and vulnerabilities driven by software dependencies, and cost growth to sustain software intensive systems, all in the era of declining IT talent.

Lastly the DSB points out that the “tyranny of time,” caused by rapid IT technology change and shortened military commander decision timelines, is driving IT acquisitions toward shorter delivery times, if they are to be relevant.

So how could DoD and Navy reverse this negative spiral?

The German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) is often referred to as the father of bureaucracy because he was the first person to characterize the nature of large, complex organizations often found in government, institutions, or large corporations. The term bureaucracy has no positive or negative meaning even though we generally use the term negatively when referring to organizations that are process driven and slow to address new ideas or non-standard requests.

Max Weber argued that bureaucracy constitutes the most efficient and rational way in which human activity can be organized to maintain order, maximize efficiency, and eliminate favoritism. At the same time Weber also saw bureaucracy as a threat to the organizational growth needed for an institution to remain effective. To counter this downside of bureaucracies, he wrote that charismatic leadership is needed to break-down bureaucratic impediments. He described charisma as:

Max Weber argued that bureaucracy constitutes the most efficient and rational way in which human activity can be organized to maintain order, maximize efficiency, and eliminate favoritism. At the same time Weber also saw bureaucracy as a threat to the organizational growth needed for an institution to remain effective. To counter this downside of bureaucracies, he wrote that charismatic leadership is needed to break-down bureaucratic impediments. He described charisma as:

“A certain quality of an individual personality, by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with… specifically exceptional powers or qualities.”

From his work, charismatic authority or leadership has become recognized as:

“Power legitimized on the basis of a leader’s exceptional personal qualities or the demonstration of extraordinary insight and accomplishment, which inspire loyalty and obedience from followers.”

We can recognize the value of Weber’s ideas because the U.S. Navy has a rich history of charismatic leaders who have radically advanced Naval warfare capability. Examples are:

Admiral Hyman Rickover’s leadership that built the world’s first nuclear submarine capability;

Admiral William Rayborn’s leadership that built effective submarine  launched nuclear ballistic missiles;

launched nuclear ballistic missiles;

Admiral Wayne Meyer’s leadership that built today’s AEGIS fleet; and,

Admiral Walt Locke’s leadership that built the Tomahawk cruise missile capability [picture not available].

These men were all charismatic leaders who were able to transform Naval warfare despite the bureaucratic processes in which they had to work. In each case these leaders were dogmatic about delivering good capability quickly in support of the military need.

Today’s DoD/Navy IT acquisition is in need of charismatic leaders!

What might a charismatic leader building new IT capability cause to happen today? There are many proven best practices for building and delivering good IT systems. We inherently know this to be true because commercial IT companies deliver effective IT infrastructure and applications across the commercial landscape almost daily. Unfortunately these best practices are not aligned with the requirements, budgeting, and acquisition oversight processes institutionalized within the DoD. It is interesting that changing the way the DoD acquires IT capabilities does not require laws to be rewritten. It does require charismatic leaders to implement these best practices while paving the way for a new set of bureaucratic processes that are better aligned to proven IT development best practices.

A charismatic leader would likely do so by:

- Demonstrating to the warfighters and requirements controllers that a small set of high level general requirements can be effectively refined into relevant detailed requirements through six month incremental deliveries of useful capabilities that have been driven by continuous interactions with the warfighters.

- Demonstrating to the budget process controllers that today’s IT systems must be continuously improved and upgraded to counter cyber security threats, while pacing the changing capability needed by the warfighters.

- Demonstrating to the acquisition input measuring oversight controllers that delivering useful capability in six month increments can consistently deliver required performance, on schedule, and within cost.

- Demonstrating to industry partners that government integrators, working with high quality industry IT developers across multiple teams, are capable of delivering monthly builds that support early testing and cyber security reviews so that six m0nth operational deliveries easily achieve full cyber security and test and evaluation certifications.

- Continuing this IT development cycle until the budgeting process, to include Congress, understands that all future IT capabilities must be continuously built and delivered this way.

Fortunately this set of best practices is easily accomplished with today’s software development support tools, layered architectures, and available cloud infrastructures. If charismatic leaders do not emerge to continuously deliver timely IT capabilities, our Country is on track for the DSB’s words to become true:

“The inability to effectively acquire information technology systems is critical to national security. Thus, the many challenges surrounding information technology must be addressed if DOD is to remain a military leader in the future.”

Good work, Marv. Surprised you didn’t include Adm Jerry O Tuttle and his leadership for commercial off the shelf IT products.

Carl

Carl, good point on Jerry. He certainly helped put IT on the map, as did Archie Clemins. Todate we haven’t had an IT event that has equated to the level of change as cited. But we are at a place in history where and equivalent of nuclear powered subs is needed in the IT business.

Bravo! Marv puts forth a balanced and compelling analysis that sounds a needed alarm.

Here Marv captures key insights and assembles them together as puzzle pieces to show a seldom seen big picture. This paradigm has application well beyond the U.S. Navy and is something that many people are unknowingly a part of, with no clue as to the unintended opportunity cost of their fervent efforts. ICT investment is particularly challenging because of the need for breakthroughs, mounting gaps in security performance, and strategic importance in mission critical functions in business, military and other organizations.

Karl, nicely stated… These ideas do apply to all things bureaucratic…

Marv,

Great post.

The only thing that you do not seem to highlight is the fact that without the ability to rapidly get new folks on contract and to modify existing contracts, the six month refresh that you propose can drag out quite a ways.

Basically, your high refresh rate, iterative model will require educating many for folks who believe that IT requirements can be identified a long way into the future, like for ships.

Frank Fernandez

Frank, you are dead on… The reason I continue to push for “speed to capability” as the primary acquisition metric is because everyone in the chain of events should be measured on speed to capability and particularly the contracts shop, the legal shop, and the acquisition watch dogs… Cost, Schedule and Performance should be the second tier metric in our IT business…

Marv,

Your last comment is the essence of this entire chain for two reasons:

1. The functions you cite are the areas that must be addressed

2. This simple statement of Speed to Capability over CST performance as a metric can become the tag line. You all are addressing a very complex and daunting challenge and your thoughts here simplify it in a manner that allows an actionable strategy to be developed with measurable results. Metrics that should be measured from program conception, not Milestone B.

Great insight!

-Stuart

Good points Stu. The reason I like “speed to capability” is that overall we get what we measure. We need speed to capability but because it is not measured it is the last thing we get unless we are purchasing new capability during a war…

A couple of years ago I visited the branch and division at the lab and was taken aback by the amount of paperwork and spreadsheets that is required for projects and programs. Years ago we where able to react to changes and use updated technology with out all the paperwork.

We did this with leadership not paperwork.

Jerry, amen!! well said. Unfortunately, our young leaders today have never experienced what you speak of…

Marv,

Great thoughts. I would also add like to your list of U.S. Navy leaders who changed the Navy for the better; Admiral Grace Hopper. A charismatic leader who challenged traditional thinking and put service to county over personal gain. As we examine ways to maintain and in some cases widen the technological gap our forces enjoy over potential adversaries, her approaches to technology problem solving become even more compelling and worth emulating.

Thanks

V/r

Kurt

Kurt, great thought… I wasn’t trying to highlight our IT charismatic leaders but you make the case that Grace Hopper was certainly a game changer for IT as has been Admirals Jerry Tuttle, Art Cebrowski, and Archie Clemins. Thanks for catching the oversight…

Marv has hit the nail on the head. The current process encourages and rewards process adherence over outcomes. I would add one twist to Marv’s comments–we need IT leaders who understand, and are able to show, how IT can drive mission and business results. The current crop of “non-leaders” get into the “techno speak” of budget reductions, virtualization, cloud, identity management, etc, etc and manage to speak without a single word or sentence that talks, in plan operational tems, about how the IT investment can drive mission results, national security, or improve citizen services.

Thanks Bill, excellent point that our leaders must always revisit… The master of this idea was Admiral Art Cebrowski…

Harvard Business Manaement

CHANGE MANAGEMENT

Innovating Around a Bureaucracy

Brad Power

MARCH 8, 2013

What do you do if you’re a leader in a large, successful organization with an entrenched bureaucracy, and you see the need for innovation? Can you change the way a large organization — such as the federal government — does its work, when all the forces are arrayed for stability and conservatism?

Consider the story of the Business Transformation Agency of the Department of Defense, which was founded in 2005 under Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, and “disestablished” in 2011 by Defense Secretary Gates. The Business Transformation Agency was populated by people brought in from the commercial sector. They were bold and brash and injected fresh new ideas that challenged existing policy and practice in many quarters of the Department of Defense administration (such as finance, human resources, procurement, and supply chain processes). They ran into many of the familiar challenges of making changes in the federal government: the difficulty of firing; the complexity of hiring at many levels of management; the need for contracts to be put out for competitive bidding; multiple stakeholders including civil servants, appointees, contractors, regulators; and Congress to be considered in almost all decisions. Unlike at commercial companies, there was no senior leader who could mandate changes. The Deputy Secretary of Defense that originally sponsored the agency under Rumsfeld left, and the new leader was less enthusiastic, ultimately leading to the agency’s demise. The entrenched culture of the Department of Defense defeated attempts to change it.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), however, was successful in transforming its bureaucracy. The IRS had two advantages: Congress provided a strong mandate for change (the U.S. IRS Reform and Restructuring Act of 1998); and an outstanding, senior executive from the private sector, Charles Rossotti, was appointed for a five-year term to drive the changes. Under Rossotti’s guidance, the IRS reorganized from a geographic structure to four new customer-oriented operating divisions. IT also upgraded old technology and processes, achieving significant improvements in service and compliance. For example, it implemented an Internet service that answers the question “Where’s my refund?” that has had over one billion hits and freed up 800 customer service representatives to handle more complex issues.

So, what makes the difference between success and failure? Based on long experience working with government agencies and with large organizations of all stripes, I have seen that big changes to the way work is done require:

a team of insiders and outsiders to come up with new ideas

a clear external motivation to do something

strong leaders who believe in the ideas and push the bureaucracy to implement them consistently over a number of years

Sometimes (but not often) bureaucracies do make incremental changes to the way they do work, but they are usually not sufficient to meet citizen-customer needs. An innovation team composed of the “best and brightest” (like the “bold and brash” Business Transformation Agency) can identify bigger changes, but those cannot be implemented inside a strong bureaucracy without a strong and clear motivation to change. Now, in a competitive free-market environment, a for-profit company can be motivated by threats to its survival, or by declining market share and profitability. The big challenge for a government agency, however, is that the motivation needs to be a congressional or administration mandate. I’d like to tell you there’s another way to motivate change in case you don’t have such a mandate, but in the extreme environment of an entrenched bureaucracy, I haven’t seen it. Thus, needed process changes within bureaucracies should always be built into such initiatives. Probably most important, though, as in the example of the IRS, a senior leader is absolutely essential to drive the change and sharpen the organization’s focus on citizen-customers — to overcome the natural tendency of bureaucracies to focus internally. And as the IRS and Department of Defense stories illustrate, the bureaucratic ship won’t turn on a dime — leaders need to sustain focus on the changes over the long term, likely for five years or more.

Leaders of big bureaucracies need to get — and keep — everyone enthused, create and communicate a future vision, assure support during the transition, insist on excellence, create demands on managers, and convince everyone of top management’s conviction and commitment to change. These leadership challenges may seem familiar, but in a bureaucracy they are, if anything, magnified. To sustain momentum in this special context, leaders may need to adopt the behaviors of a fanatic — as Winston Churchill said, “A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.”

Of course, the federal government provides an extreme example of entrenched bureaucracy with an established way of doing things. But it offers lessons to any organization that is mature, successful, and set in its ways, yet recognizes the need to transform itself.

Brad Power has consulted and conducted research on process innovation and business transformation for the last 30 years. His latest research focuses on how top management creates breakthrough business models enabling today’s performance and tomorrow’s innovation, building on work with the Lean Enterprise Institute, Hammer and Company, and FCB Partners.

Christopher, good add. Brad does a good job of exploring these challenges. Related to his points about the need for a team of insiders and outsiders, clear external motivation, and great leaders, I couldn’t agree more. The reason that Admirals, Rickover, Meyers, and Locke, from my examples were fired by Navy in the end is that they were well connected to Congress which provided the power and budget to move the “external motivation” forward. Their expertise was knowing how to build and direct this “team of insiders and outsiders.” To date we haven’t had the “clear external motivation” in our IT world but the cyber security problem may yet deliver up that situation…

Marv is correct in his analysis as well as in the comment that a forcing function, a “cyberstrophic” (my term) event that significantly impacts DoD, will be required to jolt IT into the forefront of leadership thinking. Without a forcing function, it is entirely understandable why IT is not a leadership priority (case in point: the Navy’s lengthy rollout of CANES).

Why is IT not a military priority?

IT is ubiquitous. Embedded in nearly every device we use, essential to our communications and at the core of our weapons systems, it has become as critical to our military operations as fuel, food, electrical power, and water. And, like those essentials, IT gains leadership attention only when it’s absent; if it’s working, there are far more urgent activities to attend, such as how to deal with ISIS.

IT—you can’t fly it, drive it across the battlefield, or shoot it. It’s not likely we’ll see a Silver Star awarded for fighting off a cyber attack. In addition, to the military, being an IT professional is not a path to becoming Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

So, to Marv’s other point, if IT naturally is in the priority backwaters, who else is there? The bureaucrats (term used pejoratively), both military and DoD civilians, are, of course. Floating outside of the current, they have plenty of time to paddle around tweaking requirements, writing RFPs, laboring over proposal evaluations (244 days to award a contract), and so on. It’s a perfect place for them to be. Meantime, out in the channel, the commercial technology craft go whizzing by.

About leadership: We may not see charismatic leadership until (not if) the “cyberstrophic” event occurs, but when it does, history has shown that it is likely that a natural leader will arise, along with funding and urgency (remember the MRAPS?) BUT—as long as the military makes its most important IT and acquisition professional positions, such as the commander of the Navy’s SPAWAR, pre-retirement assignments, that leader most likely will NOT be an IT professional.

Goog points Tom. Thanks for jumping in.

Marv

Thoughtful and compelling. I certainly agree that those you cite as well as others mentioned in the comments are excellent examples of how charismatic leadership can lead to extraordinary results, but the reason your are writing this is because the bureaucracy is trigger loaded to strangle charismatic personalities as “mavericks.” As you point out does running DoD IT acquisition have to become more impressed with “outputs” vice process driven “inputs.” All of the charismatic personalities cited had two other personality attributes that contributed to their success: persistence and more concern for the outcomes they sought than for their own career advancement. So besides charismatic leaders to advance IT capabilities (which are really the foundational technology for command and control) flag officers and senior civilians have to nurture and protect these rare personality types from the anti-bodies in the bureaucracies who naturally there to wipe them out. joemaz

Good points Joe. And the issue becomes that mavericks that are not promoted, because of our conservative promotion system, never have the chance to be in positions of significant power. I also think that we have a risk averse officer corps that started to turn south after Tailhook. All the more reason we need charismatic leaders to step up in our too slow acquisition system.

Marv, I think another key point is integration and understanding warfare platforms. A modern day aviator or SWO will not be successful in their career without understanding each other’s capability and community. The same thinking should apply to cyber and IT. Recently, there was a very large cyber exercise where very smart cyber people were talking to very smart cyber people about cyber – and no real interaction with other components. An action needed by the charismatic leaders of today and tomorrow is to drive the importance of cross platform understandings with cyber and inculcate the criticality of space, EW and cyber in modern warfare. Until the customer understands the product and the producer understands the customer, the business will continue to fail.

Marv, you hit the nail on the head again. I would like to encourage others to also review IT-AAC’s report to congress that you contributed to, along with some 16 other thought leaders like yourself. Senator Levin agrees with our position, and has already drafted 2015 NDAA Sect 805 which puts pressure on OSD to implement Agile and Streamlined Acquisition for IT intensive programs. Our work was also incorporated into NDIA’s recent submission to congress covering the entire landscape, not just IT/Cyber.

The Navy and DoD at large must recognize that we are no longer the source of innovation nor unique in our requirements. Nearly every major IT program failure failed to tap into commercial IT standards, innovations and lessons learned driven by a $3.8 Trillion Global IT Market. The Defense Industrial Base collectively represents less than 1/2 of 1% of the market.

Marv – As aways, an exceptional thread. I’d like to expand a bit on a comment that Bill Donahue makes, “I would add one twist to Marv’s comments–we need IT leaders who understand, and are able to show, how IT can drive mission and business results.” As I work with government organizations today, I note that the divide between the Acquisition folks and the mission folks couldn’t be wider. Acquisition does things to minimize the chance of a protest of their “perfect” selection process, and the Mission input is many times nowhere to be found. So we get great process, but high probability that we deliver something other than what Mission needs–relevance, speed, effectiveness, etc. In my humble opinion, the great leaders you identified all had domain knowledge that shaped their sense of purpose and urgency. It wasn’t just “another acquisition”, it was an acquisition that would enhance capabilities in a marked way–they really did move the needle (to use overused contemporary language). They recognized what was needed, “then” set about to make it available in a time frame when the solution was still relevant. We can learn a lot from them.

Dick, your domain knowledge points are excellent and something that I took for granted but didn’t call out. Thanks for that because it is also one of the challenges we have in our IT domain. Our two best Navy examples of good leadership and good domain knowledge are Admiral Jerry Tuttle and Admiral Archie Clemins. Both leaders did not inherently have domain knowledge but they made it their business to get smart on IT and to surround themselves with other smart IT support staff.

Marv,

Excellent insight to the acquisition system as it is and its inability to rapidly respond to changing IT.

An additional perspective may be identifying the driver of the great acquisition successes led by those identified. These individuals were leading revolutionary system acquisitions that had as a minimum a service or U.S. defense priority and also national priorities. The threat to our country posed by the Soviet Union was a recognized national threat. The nuclear submarine, submarine launched ballistic missile, and the Tomahawk cruise missile (land, air and sea; conventional and nuclear warheads) were considered components of responding to the Soviet military. Historically add to that other rapidly acquired systems such as the U.S. space program, nuclear weapons, the DEW Line, SOSUS, and even the interstate highway system. The WPA is an example not of national defense but of a national priority. Public sentiment was strongly behind these programs in general even if they were unaware of the specific programs because of classification. Through these shared national priorities there existed political and military support for, action by, and thus tolerance of the leaders of those programs.

IT is so much a part of the daily lives of individuals that it’s possible IT is not seen as a national priority. The average citizen probably does not know and would be surprised to find out that many of the IT capabilities they have in business, social life, and private life have not transformed into synonymous DoD systems and capabilities as rapidly as outside of DoD. Without the concern of the average citizen, it’s hard if not impossible to generate the priority that would encourage or permit the actions of activist acquisition leadership and make real changes to the bureaucratic acquisition process.

One would assume that cyber threats would generate social concern. However, the relative lack of indignation or fear by the general populous over recent cyber incidents such as the Target or Home Depot disclosures indicates otherwise.

Society has wrapped itself with an IT and cyber security blanket fending off the first chills of the need to take action. There is not a great nationally accepted need to acquire IT and cyber security systems and capabilities thus a driver to change the acquisition process or the tolerance of those willing to push the boundaries.

Tony

Tony, great points about how my examples were addressing National priority needs. As you point out IT should be a National priority but to date it hasn’t been understood as that. Let’s hope that we don’t have to have a cyber crisis before it becomes real…

I subscribe to the notion of “charismatic leadership” whole-heartedly. The problem is that our performance evaluation and selection systems have been watered down such that risk-avoiders get rewarded. How we evaluate people at every step of their careers is the key to obtaining the leadership we desperately need at this juncture. I repeat my prescription for how to do that below (“IT professionals” could easily be substituted for “officers” throughout, but you’ll get the idea):

I think we need what we’ve always needed, and that is innovative, dynamic and forward-thinking warfighters who are willing to take calculated risks during their careers as they push forward with new tactics, concepts and methodologies for conducting warfare on the modern battlefield. We need leaders with a broad understanding of evolving technology and its general and specific application to warfighting—men who can divine causal relationships among threat behavior, force readiness and disposition, environmental conditions, tactics, intuition, opportunity, and decisive action. What we don’t need are administrators, managers, and risk-avoiding politicians (at least not in visible positions of leadership). We need leaders who are not afraid to lead when common sense dictates a principled decision or action that is not politically correct.

Leaders are not chameleons; they adhere to first principles: duty, honor, courage, loyalty, truthfulness, and service. Their primary tactical decision aid is not a wet finger to the wind. They are about doing the right thing when nobody is looking, using the bully pulpit to change hearts and minds, and motivating their subordinates through personal example. They are visionaries who are willing to take reasonable risks to try out new ideas, and are willing to take personal responsibility for their successes and failures. They make decisions and take action for the good of the organization and the betterment of the Navy as a whole, not for self-aggrandizement or careerist reasons.

So how do we pick such men? By changing both the characteristics we seek to engender in our officers and also the fitness report paradigm itself. Here are some suggestions, beginning with the seven traits that should be documented in a fitness report:

1. Leadership. Good leadership requires a balance of results-oriented achievement and effective motivational skills. The former requires the ability to effectively set and reach difficult but achievable goals, as well as to create a vision for the entire organization within the leader’s span of control. The latter requires human behavioral skills in directing actions, delegating authority while retaining responsibility, creating a positive climate within the organization, working through and with subordinates, and developing effective reward and conflict resolution processes. A one-dimensional evaluation by the reporting senior cannot effectively measure these traits. Too often such evaluations emphasize results at the expense of evaluating an officer’s motivational skills. An input from “those led” is a critical and missing piece of the puzzle; we should be soliciting confidential inputs (detailed if necessary) from senior enlisted and subordinate officers within a given officer’s command. Our chief petty officers know effective leaders when they see them; and they know CAPT Queeg’s when they see them, too!

2. Risk-taking. Effective leaders perceive and exploit opportunities, and missed opportunities are frequently the result of risk aversion—and potentially lead to defeat and death on the battlefield! If an officer has not failed (at something), he has not pushed the risk envelope enough. This is not to say that we seek “cowboys” but rather officers who are adept at taking calculated risks to achieve what may be transitory goals and objectives. Taking personal risks is an act of bravery that motivates others by direct example; taking collective risks with an entire organization requires visionary leadership, as well as an intuitive understanding of the total organization’s capabilities and limitations. We need officers willing to take both types of risks, and we need to recognize that failures that result from calculated risk-taking should not necessarily by career-ending. Risk mitigation is partly science, partly art; it requires establishment of concrete goals and objectives, balancing of available resources, determination of priorities and critical paths, conducting of tradeoff analyses, setting of measurable interim goals, and a willingness to cease or redirect actions in order to cut losses if required.

3. Innovation. Innovation is a unique insight into the way things work (or should work!). Innovation can be technological, concept-based, process-oriented, and/or a combination of these. We want leaders who have the ability to look at the way things work (i.e., systems, organizations, platforms, and people) from orthogonal viewpoints. This requires an inherent ability to step back and look at the total perspective, whether it is how a combat system operates, how a carrier battle group staff functions, what contributes to total battlespace awareness, or how a complex combined exercise is conducted. We need leaders who are idea generators, who can conceive new tactics and procedures for using those new widgets, who continually seek opportunities for improvement, and who are aggressive in tinkering with established processes so that we might decisively move the body of naval warfighting science forward. Innovation and risk-taking go hand in hand.

4. Decision-making. Leaders take decisive actions based on experience, informed opinion and the best available information. Effective leaders must demonstrate an ability to sift through frequently contradictory information and views from both automated systems and people, to develop and evaluate a number of potential courses-of-action, to modify those plans based on emergent information, and then to act at precisely the optimum time at which to achieve the desired results. Decision-making is about making choices, oftentimes from among unattractive alternatives. The key to evaluating this trait is to analyze an officer’s performance in stressful situations, e.g., while conning the ship, standing a tactical watch during a real-world event or exercise, or in other situations in which decisive action is required.

5. Warfighting skills. These include tactical decision making under stress, effective real-time change management, good judgment, and an ability to decisively direct a team’s or multiple teams’ actions to accomplish complex tasks. It is not enough to know how a given system works; a leader must understand how and why a system is effective in a particular circumstance, and whether and how a system can be optimally employed to achieve the desired effect. A “total system” generally consists of equipment, software and properly organized human operators; a warfighter understands and exploits the interactions among these elements and is able to orchestrate the best use of all to achieve mission objectives. This requires an in-depth knowledge of threat tactics and historical information, capabilities and limitations of friendly systems and platforms, tactical employment concepts, environmental impacts on threat and friendly systems, and lessons-learned from previous similar encounters or situations.

6. Strengths. Evaluators should identify and describe the top three strengths of the rated officer as a means of breaking him out from his peers.

7. Weaknesses. Evaluators should identify and describe the three principal weaknesses noted in the rated officer as a means of breaking him out from his peers. All officers have weaknesses or shortcomings that require improvement. Requiring weaknesses to be clearly specified will result in a more careful and thorough evaluation of an officer’s overall performance by both the reporter and the promotion/selection board.

This is provocative but I’m not in agreement with everything here.

I agree that bureaucracies tend to make plans and then specify the inputs needed to achieve their plans; and if they don’t achieve plans, they say it was because some input was shortchanged. But don’t they also set milestones and keep track of how they do against their milestones?

I don’t accept the charismatic leader argument. It reminds me too much of the benevolent dictator argument. Everything works OK as long as the dictator is benevolent, but it can go badly wrong if the dictator is not. We have all too many examples of charismatic but misguided leaders who make a bigger mess of things. Our system of government is built on checks and balances so that it is much more difficult for a single person to push things wildly one way or another.

The great leaders you cited as examples were great because they were able to transform the bureaucratic system and get it to adopt new practices supported by important new technologies. They had to deal with multiple agencies and bring them and the political

system (Congress) into alignment. These kinds of leaders are unusual not because they were charismatic but because they understood the social processes of change, transformation, and resistance. Bob Dunham and I wrote about this kind of leadership in our book The Innovator’s Way (MIT Press, 2010).

Thanks Peter, it is a honor to have your expertise added to this discussion. As you well understand forward motion requires both change agents and hard nuts and bolts management style leaders so I agree that it is an oversimplification to attribute everything to charismatic leadership. While I agree that we have a system of checks and balances, my experience is that our system biases toward too many checks and too little forward motion to the detriment of our warfighting capabilities. I believe we need more change agents because we are stifled by too many that accept the status quo.

I believe charismatic leadership to me is the same as what [in your book] you call generative leadership: “Generative leaders get their power from authority granted by others. They generate followers and build more power by using their power to help others take care of what those others care about. Generative leaders regard power as the capacity to persuade and influence people to commit to a new practice. Their leadership is based on care, the most important quality for a leader to develop. – Peter J. Denning. The Innovator’s Way: Essential Practices for Successful Innovation (Kindle Locations 2956-2958). Kindle Edition.

From my vantage point as a project manager I see one big problem not addressed above. The packaging of bids from subcontractors by the primes. The evaluation process grades the total package – even though each of the subcomponents may be less than optimal. I’ve experienced contracts where proven technologies were rejected in favor of re-development because the proven technology was offered by the wrong prime. Each of the solutions offered was evaluated and the total bid package was selected on the sum of the scores. In my opinion this resulted in an average (or, in some cased, sub-par) package because each of the prime vendors was looking for the best contract, not the best system. The competition system is thus “rigged” against obtaining an optimal package. I’m not in opposition to developing new technology, but to reject things that work because they don’t fit into the bidding structure is, in my opinion – based on my experience – is most often going to result in unnecessary hurdles that need to be overcome in the development. We need to develop a better bid/award/development structure that is flexible enough to accommodate proven systems no matter which prime gets the contact.

I respectfully offer a few thoughts on the implementation challenges and opportunities that come to mind from reading your paper. I realize this will come across as either from a naysayer or someone who can’t help but play the Devil’s Advocate. I hope this is seen as “windmills that must be tilted” to help bring your concept to fruition.

While six month cycle time development should be technically feasible, agile software development model as an example, there are at least two barriers: the acquisition process including integration and certification and fielding on ships, aircraft, and systems with high operational tempo.

Test schedule and laboratory availability become less flexible the deeper one progresses in the systems of systems architecture. Individual system testing can be done at will, but certification testing involving larger network architectures are, at least today, significant events involving multiple systems from multiple program offices. It is merely my conjecture that the staffing levels are sufficient to conduct events sequentially and not consecutively/concurrently. This implies structuring all systems within the architecture to not only go to a six month cycle time, but the same six month cycle time. On the one hand, systems with varying complexity can deliver varying degrees of new capability on a six month schedule. But the economic benefit will be weighed against the cost of test and integration of what might be limited incremental improvement.

Continuous six month delivery cycle presents logistical challenges of configuration control and host platform availability. The configuration control challenge is more than just “rolling part numbers”. Opportunities to implement improvements on operational assets are necessarily driven by their operational schedule. This is just my opinion but I’d imagine Commanding Officers would be loath to change their system configuration shortly before deployment and certainly not during deployment. Thus a six month development cycle turns into something like a 12 month implementation cycle. Of course this is mitigated by implementing multiple six month enhancements whenever the opportunity presents itself. The other implication is that changes should not affect compatibility with legacy configurations to preserve battle group/SAG interoperability. Ships of a class may look the same from the outside (and even then perhaps only from afar) but differ significantly in their systems configuration. This challenge is applicable regardless of the cycle time, but increasing the various configurations may exacerbate the issue.

I would not be at all surprised if every one of the charismatic leaders discussed had staffs that were full of similarly charismatic individuals, each making a positive impact on their role and responsibilities. Moreover, if overhauling the acquisition process is “dreaming the impossible dream”, perhaps the next best thing is a team of charismatic leaders who know the process inside and out and know how to “make it work”. This is not at all implying a blind adherence to the process, but rather knowing when and how to “manipulate” the process. One example: overcoming the annualization of procurement rule based on 12 month installation capacity to accomplish a total fleet purchase for quantity of units that could compete with commercial buyers as well as realize economy of scale. To this end, one might add an additional activity to your list: instill a culture of charismatic leadership within his/her organization. Just as a ship responds with some delay to rudder input but does indeed turn, perhaps the acquisition process can similarly be changed incrementally by a team of dedicated charismatic leaders.

Thanks Mark, good comments. I did not do a good job in the post of making it clear that the 6 month capability upgrades would be focused on the applications or middleware layer of a modern SOA architecture. The challenge of improving infrastructure layers or purchasing large platforms clearly require longer time to procure, test, and certify. To your point on charismatic teams, I believe that good leaders attract and help create charismatic teams that do use the processes to best advantage.