Belt and Road Initiative, Why?

By Evan Dudik — edudik@evandudik.com

In the Panama Canal and elsewhere, China sees opportunities to leverage strategic investments.

Fast forward to recent years. In 2015 an anonymous source leaked the heretofore secret Panama Papers. The Papers documented shell companies—over 200,000 of them—shielding world power players including Vladimir Putin from scrutiny of their wealth, control of companies and taxes. One result is that Panama no longer became a favorite venue for global bankers. The leakage of Papers continues to this day (writing in mid-2019). Banking is so important to the Panamanian economy, it has looked elsewhere to replace its international banking industry. China steps in:

“… a tidal wave of Chinese investment is in the works. Major infrastructure projects and an imminent free trade agreement will allow Panama, a country of 4 million people, to maximize its potential as a hub for regional trade, manufacturing, and logistics and ease the strain on a financial services industry damaged by the Panama Papers. In return, for a relatively modest outlay, China is poised to become the most important commercial partner in a country that controls a key chokepoint of world trade.” [46].

It would be indeed ironic if the U.S.’ military commitment to defend the Panama Canal resulted in an obligation to protect an economic and foreign policy vassal of China and defend China’s de facto control of a key world choke point. It doesn’t take a huge leap of imagination to see that in the event of close-to-war tensions with China—say in the South China Sea–transit times for U.S. naval forces and supply shipments now using the Canal would suddenly become weeks or months longer. Given a slightly cautious U.S. president advised by a cost-benefit State Department mentality, no doubt a face-saving agreement along the lines of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords ending U.S. involvement in Vietnam would ensue. Would any American want to go to war over the Canal? It would be worth a PhD thesis to discover how many years (or months) Henry Kissinger’s canal-for-goodwill bargain yielded a net benefit for the U.S.

We’ve already mentioned the BARI’s toehold in Europe. In particular, China has contracted with NATO member Italy to invest in several Italian ports.. Working on a Saturday, Italy joined BARI officially on March 23 as Italian Premier Giuseppe Conte signed the paperwork with President Xi Jinping in Rome. China aims to expand this beachhead. Poorer European nations, particularly countries such as Greece, Serbia, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro, weary of looking West for investment are welcoming the Chinese overtures. [47]

Other European powers, particularly France and Germany express caution—but not, as we’ve mentioned the more enthusiastic Netherlands, Belgium and the Czech Republic. It would be difficult for the elected leaders of these countries to spurn what seems like a low-cost, low-risk way to tap the growing Chinese middle-class market.

Then there’s Russia. Russian academics debate whether Russian and Central Asian involvement with BARI is benign or dangerous for Russia’s security. The ‘pro-BARI’ faction emphasizes that China could help Central Asian countries and perhaps Russia itself develop their vast natural resources. The “anti-BARI” group emphasizes the potential for BARI to rope Central Asian (and other near-abroad countries) into China’s orbit and out of Russia’s sphere of influence.

Both are correct. However, never was the military maxim to judge adversaries not by their intentions but by their capabilities more applicable. Successful and permanent BARI initiatives in Central Asia would tip the balance of influence toward China. Whether China intends this result is but marginally relevant, particularly as Russia is in no position militarily to eject the nose of the BARI camel once it’s under the Central Asian tent. Nor is it today in a position to compete with China, in contrast unlike the halting steps of Japan, Taiwan and Western nations to provide investment alternatives to BARI’s siren song.

How does BARI and relationships with Russia fit into China’s Grand Strategy? Robert Sutter of the National Bureau for Asian Research (NBR) puts the matter succinctly: “Good relationships with Russia naturally assist China in isolating the US. Common interests, opposition to U.S. pressure, and the perceived decline of the West have prompted Russian-Chinese relations to advance in ways that seriously affect the interests of the United States and its allies and partners. Russia and China pose growing challenges to the U.S.-supported order in their priority spheres of concern—for Russia, Europe and the Middle East, and for China, its continental and maritime peripheries. They work separately and together to curb U.S. power and influence in the political, economic, and security domains and undermine the United States’ relations with its allies and partners in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. These joint efforts include diplomatic, security, and economic measures in multilateral forums and bilateral relations with U.S. adversaries such as North Korea, Iran, and Syria.” [48].

China’s long-term Superstrategy likely includes a dominating relationship with Russia plus vassalage of what is now Russia’s ‘near abroad’, Central Asia and eastern and southern Europe. Easier access to the one thing besides weapons Russia creates in quantity, gas and oil would be a plus for China But the big idea is to create hegemony over what Mackinder called the ‘world island’. With Russia as a firm if junior partner, Beijing would indeed be in a place to dominate the world. We could try and comfort ourselves that the mutual historic suspicions of Russia and China preclude the emergence of this unipolar world. Nay-sayers could also point to the adverse demographic trends in both countries. Surely, they are in a race against time. Nevertheless, this formidable combination must be too attractive to Beijing for the CCP to pass up the opportunity. The low level of risk to China provides additional incentive: So what if Russia under Putin doesn’t play ball. The next autocrat will.

We could go on to discuss BARI in the Middle East and Africa. I’m afraid the story would be exactly the same.

Instead, however, it’s worthwhile to gather together the threads of Chinese goals for BARI materializing from our discussion:

- Control the world’s maritime trade choke points.

- Not just the chokepoints. Establish venues for originating disruption close to US and its allies’ population and transportation centers, to be used when the time comes. In the meantime, make money if convenient. If not

- Secure China’ energy sources in ways the U.S. can’t disrupt. Accomplishing #1 helps greatly to achieve this goal. Securing the apparent undersea petroleum riches in the South China Sea is another step toward Chinese energy independence while denying US ability to interfere. BARI in Latin America (particularly oil-rich and capital-poor Venezuela) has the same aim [49]. As part of BARI, and attractive to Thailand, China aims to build a canal across Thailand’s Kra Isthmus to link the Gulf of Thailand with the Andaman Sea. While this would cut a few day’s transit time between China and India, the real purpose seems to be to provide a Chinese-dominated way to import oil without depending on access to the Malacca Straits—where tankers sail under the noses of the U.S. Navy.

- Contain Russian power by coopting and replacing the Russian “near abroad” Central Asian countries while accessing their markets, minerals and energy resources. If Russia itself agrees to BARI investment so much the better—not excluding a possible debt trap. For example, Russia could use help improving declining yield of its oil fields, Russia’s primary means of earning foreign exchange.

- Wean Europeans from their traditionally tight relationships with the US.

- Employ surplus Chinese labor, that is, China’s lumpenproletariat, an ironic twist for China’s Marxist beliefs

- Expand use of the renminbi in as many countries in the world as possible, replacing the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency and replacing Western-centric international funding organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the giant, the European Investment Bank (EIB). [50]. It’s easy to imagine a chronically capital-short country such as NATO member Greece turning to China for BARI investments beyond Athens’ port of Piraeus .

- Reestablish the glory and power of China past by using unsustainable debt to make as many countries as possible vassals worldwide.

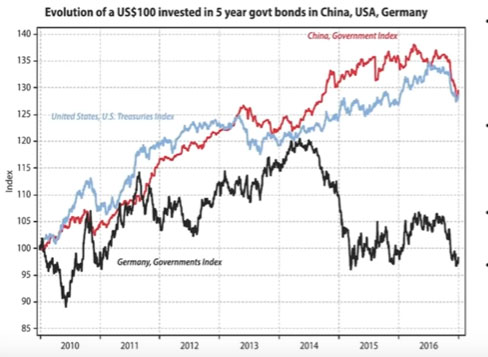

Just to expand slightly on point 7, see the following graph.

This graph shows that China has succeeded in providing a return on its government bonds competitive to the U.S. despite complaints that it has devalued its currency to gain trade advantages. This policy helps make the renminbi a viable alternative to the U.S. dollar [51].

Now that you know the key elements of China’s strategy to make its mark on the world, stay tuned for a summary of how it will carry out this strategy.