“…sustaining exaggerated acquisition timelines in the name of good public stewardship has become an embarrassing National failure.”

“…sustaining exaggerated acquisition timelines in the name of good public stewardship has become an embarrassing National failure.”

In my opinion there are two primary issues damaging our Nation’s future defenses!

- Loss of technical superiority – bureaucratic acquisition processes are breaking the bank while doubling or tripling system development and delivery times; and,

- Smaller numbers of military platforms –American taxpayers are spending too much to get too little military capability.

This is not news to the defense department. Over the past two decades, hundreds of studies and reports have identified causes and recommended changes. To date, no effective action has been able to reverse the trend. In April 2009 the Defense Science Board study, Creating a Strategic DOD Acquisition Platform stated:

“Typical major system acquisitions take 10 to 15 years, while new product development in the commercial sector of similarly complex systems takes one-third to one-half of that time.”

…” the nation faces very adaptive adversaries. The United States is no longer in a unique position of technological supremacy. Many types of advanced technology are readily available on the world market.”

Unfortunately this reality has been self-inflicted in the well-intended name of good public stewardship. The acquisition bureaucracies (to include Congressional committees) have attempted to fix every acquisition cost, schedule, or performance failure with additional rules & oversight constraints. One only need look at history to understand the extent of our current crisis:

“In July 1951, the U.S. Congress authorized construction of the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, under the leadership of Captain Hyman G. Rickover, USN.”

“In July 1951, the U.S. Congress authorized construction of the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine, under the leadership of Captain Hyman G. Rickover, USN.”

“The Westinghouse Corporation was assigned to build its reactor. After the submarine was completed, Mamie Eisenhower broke the traditional bottle of champagne on Nautilus’ bow. On 17 January 1955, it began its sea trials after leaving its dock in Groton, Connecticut. The submarine was 320 feet long, and cost about $55 million.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_submarine

To develop and deliver the world’s most technically sophisticated submarine in three and one-half years for the cost of $470 million (2012 $ equivalent) is laughable today.

By contrast the DoD’s newest combat aircraft, the F35 Joint Strike Fighter, began development in 1993. Since that time cost, schedule, and performance issues have delayed development and fielding.

By contrast the DoD’s newest combat aircraft, the F35 Joint Strike Fighter, began development in 1993. Since that time cost, schedule, and performance issues have delayed development and fielding.

“As of April 2010 the United States intends to buy a total of 2,443 aircraft for an estimated US$323 billion [equates to $132M per aircraft], making it the most expensive defense program in US history.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_Martin_F-35_Lightning_II_procurement

Following the success of early programs like the Nautilus submarine, acquisition process began to be formalized around the measurement of cost, schedule, and performance as primary decision metrics. These same metrics are the current program foundation for all of DoD’s acquisition programs. Interestingly, to my knowledge, these metrics have never been examined as contributors to the problem.

While supporting a recent acquisition reform study, I began to ponder the potential impact of changing the primary acquisition metrics from cost, schedule, & performance to speed to capability. When one considers that speed to capability is critical to successful military deterrence, it is not a stretch to understand that cost, schedule, & performance are of secondary importance. Measured correctly, this single metric could have game changing impact just as did John F Kennedy’s call to safely put a man on the moon by the end of the decade.

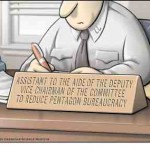

Building transparency around everything that reduces speed to capability, would allow bureaucratic processes to be exposed and corrected. Most acquisition delaying activities are never assigned culpability. Examples include:

- Congressional budgeting delays that prevent funds from being efficiently expended;

- Contracting offices that delay contracts in the name of fairness and legal constraints;

- Budget categories, meant to prevent misuse of funds, that bottleneck contract expenditures;

- Independent requirements processes that define requirements outside the art-of-the-possible;

- Senior acquisition milestone reviews requiring hundreds of “stakeholder in the loop” briefings (read that non-productive weeks);

- Integrated Product Teams that enable low priority concerns to hold up program milestone decisions;

- Cost overruns driven by delayed milestone reviews;

- Reduced production quantities driven by cost overruns;

- Independent and inconsistent information assurance (IA) processes that substitute process for effective IA;

- Lengthy and expensive independent Test & Evaluation processes that still authorize ineffective equipment to be fielded; and,

- …. this list could go on and on!

Alternatively, if every organization involved with an acquisition program were transparently measured and rewarded for demonstrated speed to capability then delaying processes would be prioritized in terms of lost time, lost operational capability, and ineffective cost growth. Managed appropriately, these metrics would reward managers that moved processes quickly while weeding out those that allow lower priority issues to trump delivery time.

Speed to capability is always the primary metric during war, just as it was in the recent gulf wars. A good example is the U.S. Army’s Kestrel persistent ground surveillance system that successfully supports the Afganistan war effort.

Speed to capability is always the primary metric during war, just as it was in the recent gulf wars. A good example is the U.S. Army’s Kestrel persistent ground surveillance system that successfully supports the Afganistan war effort.

“…Kestrel, birthed out of an Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Task Force initiative for protection of forward bases, was developed within 12 months.”

http://www.armytimes.com/news/2012/04/army-blimp-system-360-degree-surveillance-041612w/

The commercial markets have always understood that time is money. Speed to market has always been the metric that drives commercial high-technology products. In this age of Internet transparency, speed to market has become even more critical, as the U.S. finds itself competing with high technology products from around the globe!

Considering the instabilities that face our planet’s future, sustaining exaggerated acquisition timelines in the name of good public stewardship has become an embarrassing National failure. The April 2009 Defense Science Board said it best, but that call to action has yet to create effective change:

“Fixing the DOD acquisition process is a critical national security issue—requiring the attention of the Secretary of Defense. DOD needs a strategic acquisition platform to guide the process of equipping its forces with the right materiel to support mission needs in an expeditious, cost-effective manner. The incoming leadership must address this concern among its top priorities, as the nation’s military prowess depends on it.”

Good stuff, Marv. As you articulate, we NEED a highly vocal and active (in your face) champion on this subject. It is long over due. Keep fighting the good fight. //jpd2

While there is a great deal of truth to what you say, there is also a significant danger. Many time, quick and dirty prototypes are rushed into the field, but these prototypes were not developed with extensibility, maintainability, etc. in mind. The architectures are very brittle and the documentation is often incredibly incomplete. Thus, the systems cannot be maintained and extended. They may get to the warfighter rapidly, but new additional capabilities do not get to the warfighter rapidly. As with most topics, a middle road is optimal. While we need to be much more agile, we also need to be building on a foundation that supports future agility.

All true Donald. So that need is to find some level of balance to fast but also reliable and supported. By using prototypes as we do in war, we take a chance but we also find out which systems need to be refined into full up operational systems…

Right on! In government, as in business, everything becomes what it is measured by. Measure the wrong things and you will get the wrong outcomes. Measure the right things, and hold accountable those who don’t measure up, and you will begin to achieve the right outcomes. The government, particularly The Congress and The Executive branch get free lunch cards every 2, 4, or 6 years, and are not accountable for anything. On January 17, 1962 Kennedy gave federal employees the right to unionize and through collective barganing these rights were expanded to make it virtually impossible to fire a federal employee for incompetence. Hence public employees at all levels are not accountable for anything. The current focus of Congress on the budget dilema and the Sequester is addressing the symptoms, not the root of the problem. Federal employees who are determined to be incompetent (by means of a 20% per annum Jack Welch-style weed out process) should be fired. And the consequences of laws passed and budgets delayed should be objectively measured by an independent review board so the costs of delays, regulation, misregulation can be objectively measured, reported to the public, and those responsible removed from office.

After working as a the CTO for SPAWAR for ten years, I heartily agree with your assessment of the acquisition process. Here is the introduction to my book on innovation which will be completed this fall:

INNOVATION: From Theory to Prototype

Chapter 1

Introduction and Overview

As a naval officer I have always been on the leading edge of technology development. In the operational submarine force, we deal in warfighting capabilities not the legal niceties of a formal laboratory. Before my deployment to the Mediterranean Sea in a new construction Los Angeles Class fast attack submarine, USS Baton Rouge (SSN 689), I thought it might be prudent as the ship’s Navigator to take a backup navigation system to the new development dual miniature ship’s inertial navigation system (SINS). We purchased and took with us a yachter’s Loran C commercial system that we had been able to connect to the antenna on the periscope. It was given that it was somewhat of a jury rigged arrangement but it was critical to our successful operations when both Ship’s Inertial Navigation System (SINS) were out of commission during a two week NATO exercise. Would that be classified as innovation or just redundancy?

When our torpedo fire control system became inoperable during the first part of a three-month patrol on a ballistic missile nuclear submarine, we were unable to protect our ship from enemy attack. Three electronic chief petty officers and I sat at the wardroom table and reviewed the blueprints of the system. We were inoperable due to the failure of a 5 volt power supply circuit card for which we carried no spares. We found another power supply in another section of the fire control circuitry and after verifying that it had enough excess capacity to cover both circuits, we ran a wire to feed our broken system from the operable power supply. The system worked for the next two months at sea without any down time. Is that innovation or a violation of shipyard procedures?

We had three sons and when they were little guys in elementary school we had a VCR that was in use much of the time. We also happen to have tons of Legos which they built into cars, buildings, space ships and everything else imaginable. The VCR broke and wouldn’t load the tapes, so Dad was tasked to take it apart and find out what the problem was. It turned out to be a broken plastic arm from an over anxious little guy pushing in the tape too hard. So I took the part out and tried unsuccessfully to find a replacement. So with the option of trashing the VCR and buying a new one or fixing this one, I made a new arm out of a plastic Lego piece and super glued it to the old piece. The VCR worked successfully for at least five years and Dad got the reputation of being able to fix anything even if it took a Lego. “Daddy Fix” is still a common phrase at our house even though our boys are now in their 20s and 30s.

To Invent, you need a good imagination and a pile of junk.

—Thomas Edison (Gelb, 2007)

As a professional advanced technology developer in the defense industry, I found it very difficult to find a consistent approach being used to develop new products. Obviously, when the military customer gave us a written requirement, we could build what he requested. But that wasn’t the issue in the advanced technology realm. Many of the technologies that were emerging had never been used in the combat environment and there were no written requirements for them until we had prototypes and put them into exercises to enable the user to determine how to use them. In fact, in some cases we guessed wrong on the use in the field.

While I was working in industry for seven years, I was tasked by a senior VP to find a way to demonstrate a new holographic memory storage unit that was capable of storing over 100 GB of data on a 1 cm cube. Being a holographic unit, also meant that the data could be retrieved quickly. Since this was in the late 1990’s, 100 GB was a fantastic amount. As a navigator for two different submarines I gained an immense amount of knowledge of terrain mapping. My research showed that the space shuttle had mapped the entire globe with its Synthetic Aperture Radar and the file was less than 100 GB. The file was also available through the Defense Mapping Agency. So I could put the Earth terrain map on a 1 cm cube. As a competitive technology intelligence professional, I’d also recommended the purchase of a small company with some interesting software that would enable the operator to simulate flying over the terrain map on a computer. We also made GPS receivers so I could locate my position on the map and we made altimeters so I could tell how far we were above the map. In short, with less than $200K I could put together a prototype about the size of a breadbox that would enable any aircraft to navigate by terrain contour following anywhere on the globe and never be in danger of hitting another mountain. Our management decided that it was not a good investment. Within two months after that decision, a commercial airliner ran into the side of a mountain in Columbia, South America in the fog and killed 272 people. One of our main competitors quickly fielded a system that was much less capable than our prototypes and cleaned our clock and the entire market.

I wisdom dwell with prudence, and find out knowledge of witty inventions.

Proverbs 8:12 KJV

As a result of this and other similar cases, it became apparent to me that our company didn’t understand “innovation”, especially in the advanced technology area. It was one thing to build what was requested, but a totally different process and approach to build innovative products with new technology. No market existed for the technology before it was fielded. So how do you determine that a technology is viable before spending millions of dollars on development to field a product?

So what is innovation? How do we lead our organizations to innovate? Hamel and Prahalad wrote a great book in 1994, Competing for the Future. I’ve used thoughts and items from that book for many years. They talk about the wild ducks of an organization. I’ll admit that I’ve been called a wild duck, a lone wolf and many other things in my career that I won’t mention here. This quote sums up that wild duck approach.

In bureaucratic, hierarchical organizations employees are often like sheep. They mill around but have no clear sense of purpose. What companies need, it is often said, are wild ducks. But any duck that gets too far out of formation and can no longer benefit from the reduced wind resistance that comes from flying in formation will soon get left behind.

–Hamel and Prahalad, 1994

In attempting to put innovation into your organization you may need another analogy. I’ve found that “duck season” seems to always be in session. When you tell an experienced program manager that you are going to insert a new technology and make his life’s work over the past 15 years of his career obsolete over night, you don’t make friends. Another great book by Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma, makes this point very succinctly. So if you can’t be a duck, how do you innovate? The second analogy also comes from Hamel and Prahalad. It is the wolf pack.

In a wolf pack the leadership role is always clear, but it is often challenged and is decided based on capability and strength. The wolves are not all the same and not all are equally capable. They maintain their individuality but they are all members of the same team, and act in unison when they hunt. The reality of mutual dependency is accepted by all members. – Hamel and Prahalad, 1994

Wolves in packs are able to take down animals bigger than they ever could alone. It’s that way in innovation as well. One of my friends has worked with me so much that we frequently finish each other’s sentences. That is an innovation cell. Different parts of the group have different experiences to call upon and bring those to the group knowledge. The hardest part of innovative product development is the development of concepts of application of the new technology.

My opinion is that these cells can get too large to be effective. There are a number of texts about teams. One good one is The Wisdom of Teams, by Katzenbach and Smith. It is often referred to in innovation circles when talking about product development. Many managers that I’ve observed see value in the team itself not in the output of the team. At one of my Navy commands one manager had 87 Integrated Product Development teams (IPTs). If the number of team meetings is your metric for progress on a project, you’re not into innovation.

So what should be your metrics for measuring the success of teams? First let’s look at how we are now measuring the metrics for individuals. The metrics normally applied to all program managers are the same in almost all industries. These include cost, program and schedule. If you measure innovation by the same metrics, we almost always shut down the innovation. The reason is that these metrics all are negative for an innovative manager. Innovative product development is primarily based on risk taking. Minimizing risk is positive for each of these three metrics used for managers. There’s also often a risk matrix maintained for these managers on a weekly basis and briefed to higher management. So any manager who takes on excessive risks will by definition be rated negatively in his evaluations. The key is not to eliminate all risk it is to mitigate the risk that you have to take to be successful. One of the sayings of the Navy that I learn that the Naval Academy was this quote from John Paul Jones, who is considered the father of the United States Navy, ” He who does not risk cannot win”. To win in innovative product development you must take into account the risk required both from a technical viewpoint and from a programmatic viewpoint. There are very few no risk developments.

What are the keys to innovation? Looking at the great innovators such as Da Vinci and Edison, I would have to say the keys are permission to fail and the persistence to not quit until you finally succeed.

Thanks Stephen, sounds like your book will be a good read and an important message. If we minimize the bureaucratic obstacles and reward risk takers we will find the innovation you are suggesting.

Your post is spot-on! Meaningful measures take into account what we value… our resources (i.e. people, time, and money). For assessing where to invest our efforts and how we are progressing to delivery the capability (or requirement) must always be measured against our resources as the common denominator (e.g. capability over time, requirement per cost). I hope you publish more on this topic. The sense of urgency on this needs to resonate throughout the defense acquisition community!

If you can only focus on one thing, this is the right thing to focus on. It’s been the central point of my NPS course on “Strategy and Policy for IT Management” for nearly 10 years. During that time, things have gotten worse.

It’s not just that we’re slow, but that the opportunities are following Moore’s Law (doubling every 18 to 24 months, actually across multiple technologies not just solid state circuits). Hence, the opportunity cost of a slow acquisition process is itself increasing exponentially. That is, our distance from the frontier of what’s doable is increasing over time. We are falling further and further behind.

Focusing on just one thing is a good practice, at least till you get out of a deep hole. There are other worthy objectives, but this is the right principal concern imho.

Marv, great article and spot on. What appears to be the biggest challenge is culture. In spite of multiple congressional directives to reform Defense Acquisition, and IT Acquisition as a sub-set, few in the Pentagon bureaucracy are willing to embrace alternative approaches or thinking that might disenfranchise their personal agenda. A colleague of mine from CMU SEI recently wrote; “There is a lot of talk about agility, speed, acq reform, etc, but , in general, no one seems to be willing to take the actions needed. They would rather just talk about it. When you look at the chart that shows the DoD acquisition model (you know the one I’m talking about that looks so byzantine), every would agree that it doesn’t make sense. And from the point of SEI or IT-AAC, even if we have built a better mousetrap, it won’t matter if no one listens. Right now, I see DoD increasingly moving away from good practices, to just giving up.”

However, Frank Kendall cares, and wants to do something different and remains committed to fixing this perennial problem as evidenced by his confirmation testimony. “If confirmed, I would review the implementation of Section 804 and make any necessary recommendations for improvement. I believe many of the challenges in the past were the result of factors such as inadequate technical maturity, undisciplined or poorly understood requirements, poor configuration management practices, the lack of disciplined and mature software development processes, and shortages of qualified people.”

John, a characteristic of bureaucracies is that it becomes more easy to not push for change because that points a spot light on the change person. Many do call for change but not so much that it actually does make change. When we are part of a bureaucracy (and I have been one most of my life) life is easy because the complex process excuses us all from the blame. Max Weber, often called the father of public administration is quoted as saying that the only way to accomplish something in a bureaucracy is for a charismatic leader to rise up and step outside of the rules and process. We know that by looking at famous Navy implementors such as Admiral Rickover for nuclear Navy, Admiral Wayne Meyer for AEGIS, and Commander Walt Locke for Tomahawk. Were it not for those extraordinary efforts we would be in a different place today. There are always charismatic heroes but the deeper the bureaucracy the harder it is for any to break out…

Superb article, Marv, and excellent comments by John Weiler and Rick Hayes-Roth. Both you and I, during our days on the Navy staff…and my days on the Joint Staff…have suffered the interminable program pre-briefings that slowed the acquisition process and did little but accomplish some “happy-to-glads” in the briefing. I like making “speed to capability” a leadership and management requirement. It will take leadership and, as John indicates, a culture change achieve this. It says something to me that since we created Acquisition Professionals as a personnel management category in the naval officer corps, the acquisition process has lengthened and become more cumbersome. Culture change, leadership, and self-discipline are, to me, the key answers to this issue.

Dan, it is true that the more the DoD has focused on fixing the acquisition challenges the more it has slowed and under performed, which clearly tells us we are on the wrong path…

Speed to capability has always been the hallmark of great software product. From initial design using a contemporary architecture to management of capability to market. The problem has been fairness. The DOD acquisition process today is a cumbersome process that strives to even the playing field and accomplish the same at cheaper price. Not for the product mind you but rather by perception. Imagine if jobs were staffed with small, agile experts who were paid at rates not winnable in today’s government market. Bet you would deliver quality, long lasting software with minimal re-work, cost overruns and schedule slips and the ability for continuous integration. Measure twice, cut once…..you get what you pay for.

Marv,

The book Lean Startup by Eric Ries resonated with you terrific post. Acquisition folk are derided by the fleet, S&T community, industry as the source of our challenges, but I think these folks succeed despite the system and actually deliver some solid systems within a pretty reasonable cost in light of the challenges. However simple modifications of incentives made at the one star and below level can clear away much of our roadblocks. I do still believe the future is so bright.. shades are required!

V/R

Kurt

“As of April 2010 the United States intends to buy a total of 2,443 aircraft for an estimated US$323 billion [equates to $132M per aircraft], making it the most expensive defense program in US history.”

The above statement might be out of date – sadly, I think the costs have increased per unit

Drones & the modification of existing combat aircraft has arguably made the ‘capability’ of the F-35 dated. From an ROI view — the DoD has quite literally made the largest purchasing blunder in history.

Your post is awesome coming from someone who spent the time grinding it out in a bureaucracy; however, I’d like to point out another key indicator on ‘why’ we fail to provide equivalent disruptive tech: Lack of empathy. The commercial sector has, more often than not, a quantified connection to their customer. More empathy usually equates to more money, better product satisfaction, greater market share, etc.. Thus they have a deeply ingrained sense, or rather need to please the customer.

Defense developers couldn’t be mentally further removed from the folks on the ground and worse – they fail to recognize the need to be so, often originating from the ego-heavy, title driven DoD culture.

I wrote a blog on the topic for SPAWAR 6.0 and also published an adaptation here: https://medium.com/p/b96d7c5f221a